Our History

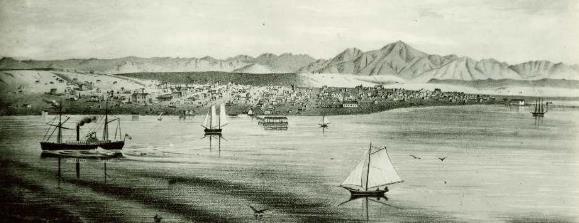

Captain Henry James Johnston came into San Diego Harbor on a regular basis back in the mid-1800s because he was the captain of the Pacific Coast Steamship Company’s S.S. Orizaba. The Orizaba was a wooden side-wheel ferryboat steamship that operated between San Francisco and San Diego beginning in 1865. Every time he came into port, the captain looked up to the barren hills overlooking the harbor. He eventually decided to purchase the land in the hope of building a home there when he retired.

On February 2, 1869, Captain Johnston bought 65-plus acres for $.25 per acre, a grand total of $16.25. Considering it to be more land than he needed, he immediately sold half of the property to his first mate Ormsby Hite for $7.50. These lands are today known as Mission Hills.

Captain Johnston didn’t live long enough to retire. He died at his San Francisco home on December 28, 1878, leaving the property to his wife Ellen Johnston. Ellen never came to see the land she owned here, and eventually willed it to her daughter Sarah Johnston Cox Miller.

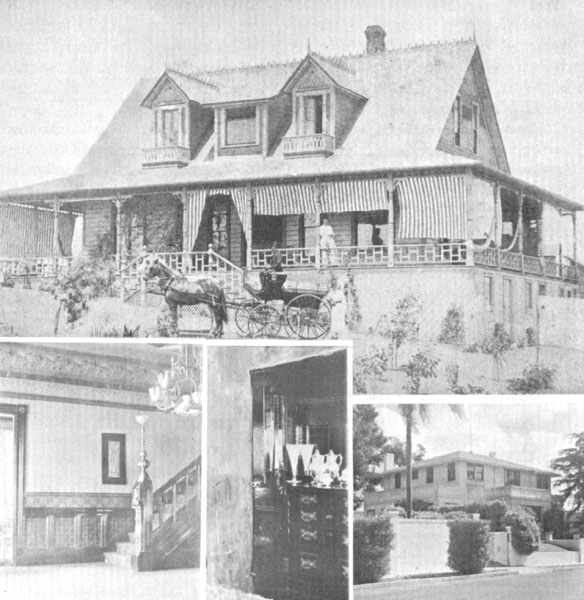

Sarah Johnston Cox Miller (married twice) came here though, and named the land Johnston Heights in honor of her father. In 1887 she built a Victorian house on the highest promontory of the land that had come from her parents. She named the house Villa Orizaba after her father’s steamship, and incorporated parts salvaged from the old ship that remain in the house today. Until 1907 the house stood amidst scrub chaparral with only a few small dairies and chicken ranches around it. An economic depression in the 1890s had thwarted efforts to develop the property into a residential neighborhood.

Sarah’s son Henry Leverett Miller wasn’t a fan of his mother’s Victorian house. He moved the house to its current location and remodeled it about 30 years after it was built. It is the historically designated Prairie style house you see today on Orizaba Street.

Henry Leverett Miller continued efforts to develop the land. He changed the street grading and the street names and redrew lot lines. He changed Johnston Road to Sunset Boulevard and named his new subdivision Inspiration Heights. He is responsible for the stucco pillars along Sunset and the iconic palm trees lining the street, all meant to promote his new subdivision.

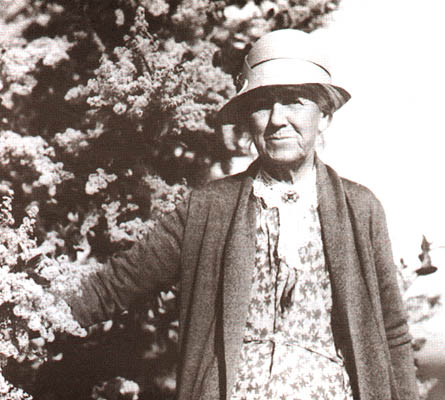

One of the passengers brought to San Diego on the S.S. Orizaba was Kate Sessions. She arrived in 1884 and became a schoolteacher at what is now San Diego High School. After being locked into a locker as a prank by mischievous high school boys, Kate decided to nurture plants rather than children. Although most San Diegans know her as the woman who almost single-handedly planted Balboa Park, she was a heavy investor in early Mission Hills property. She began buying land here in 1903 and spent the next 24 years living and/or working here. She was instrumental in bringing the trolley line down Fort Stockton, increasing the value of the property she owned and making the neighborhood a desirable place to live, one of the first streetcar suburbs.

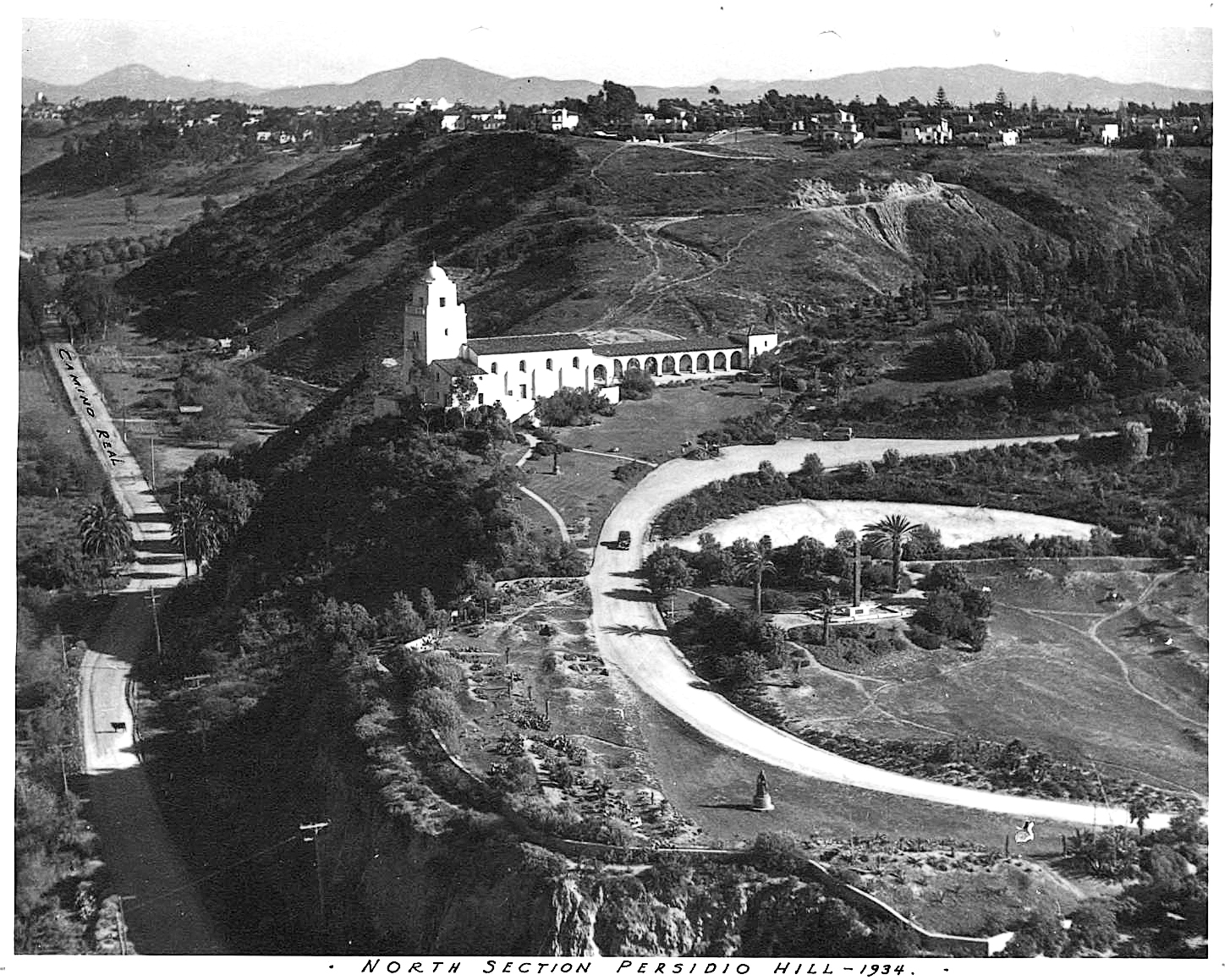

George White Marston came to San Diego in 1870 at the age of 20 and became a store clerk. He and a partner opened a general store in 1873, and when they split the business in 1878, George kept the dry goods portion. By the 1890s, Mr. Marston was a wealthy man and an influential civic-minded citizen who served on the City Council and ran unsuccessfully for mayor. As a Progressive, he worked to prevent developers and land speculators from taking over City Park (Balboa Park). George Marston purchased the land for Presidio Park, built the building and gave it to the City. His generosity and spirit left an indelible mark on all of San Diego, but Mission Hills particularly.

The Progressives believed in residential areas surrounding parks and were proponents of city planning by a landscape architect named John Nolen. Although Nolen’s plan for San Diego was never implemented because of resistance within the City, the Progressives took Nolen’s ideas and began buying up property in Mission Hills to develop the area using his guidelines. This meant a hierarchy of street widths that followed the natural terrain of the land rather than grading, filling and forcing a rectangular grid. Today our meandering streets and deep canyons are in stark contrast to the rectangular grids near Mission Hills in only slightly older neighborhoods.

John D. Speckles owned the San Diego Electric Railway Company. He was convinced that his success would depend on more riders and more fares, so he allowed his railway to expand where the real estate builders wanted it to go. The streetcar was new technology. Coupled with improvements in plumbing, sewer and water undergrounding, electricity and the telephone, there was a suburban explosion of residential building.

Mission Hills was officially born on January 20, 1908 when subdivision map #1115 was filed at the County Recorder’s Office. But it was the confluence of many events that created it:

-

- The land was ripe for development near to a crowded urban area.

- Modern thinkers with the money and influence to do so, wanted to create a model community in our city.

- The 1915 Panama-California Exposition brought visitors who wanted to live here, along with the craftsmen to build beautiful homes for them.

- Emerging technology (the automobile, the trolley, electricity, improved plumbing, water and sewer, and the telephone) made suburban living attractive and accessible.